Origins of Flora

Story of development

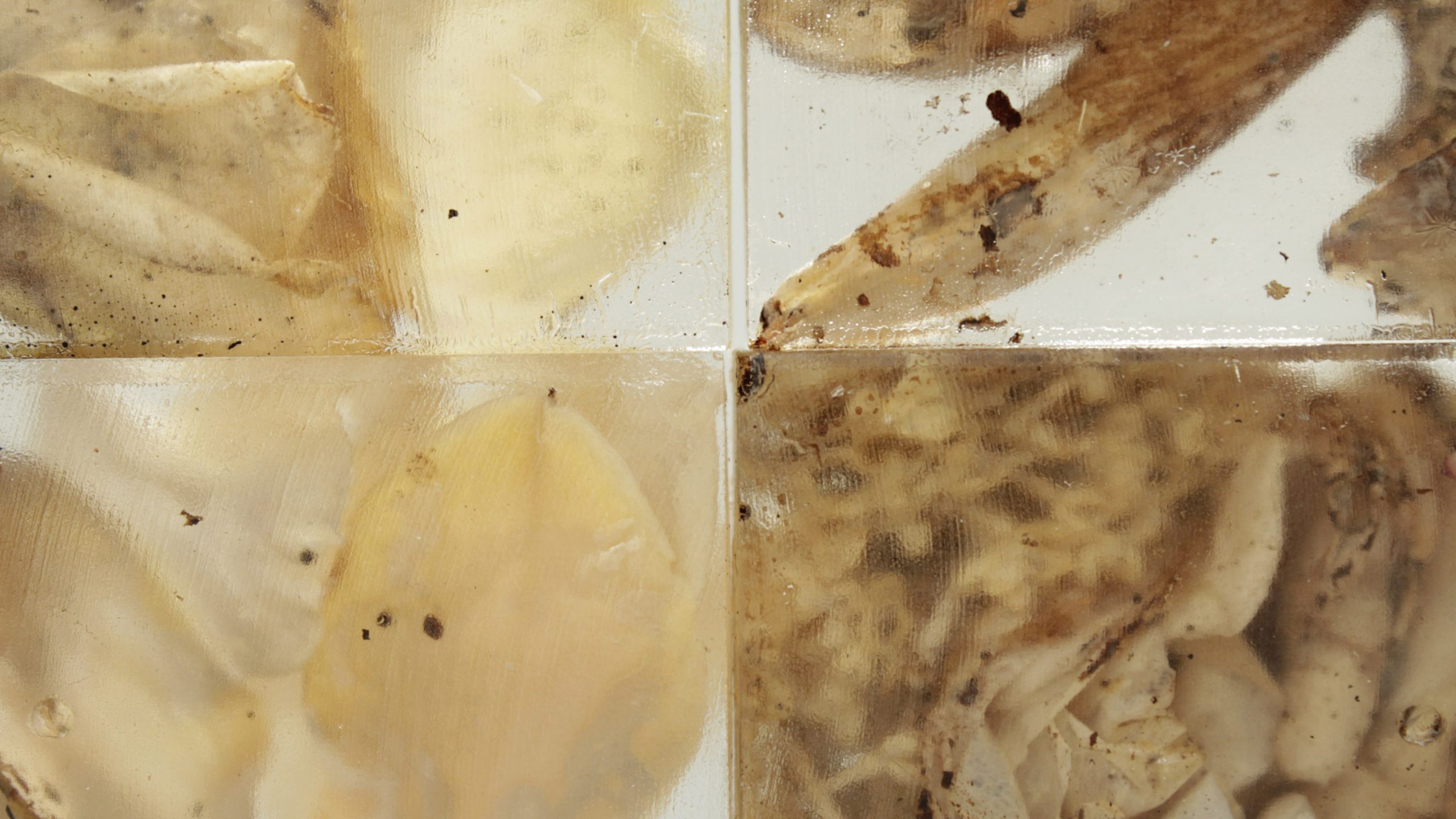

Before coming to London, I experimented with various types of resins and composites at the Design Academy Eindhoven. From the very beginning, I was interested in exploring the tension between preservation and the inherent ephemerality of the natural material.

With further development, the premise of burying a once-living matter in a solidifying composite provided a solution to preserve its beauty and make it last for centuries to come. Sealed resin provided us with the required stability and durability of the final material. An incident with tinting the resin with a black pigment altered its visual character. Waste flowers, selected for their sculptural shapes and vivid colours preserved using an array of drying and processing techniques, were submerged under the surface of resin, evoking Flemish still lifes or impressions of natural phenomena. This is how Flora came to be — a lasting contemplation on ephemerality, preservation, and decay.